I remember the moment it crept in, an intrusive thought questioning my love for journaling: “Aren’t you too old to be doing this?” But the truth is, I’m not. And neither is anyone else. As a high school Visual Arts teacher, my art journal is not only part of my everyday practice, it is central to both my pedagogy and my identity as an artist.

There’s a common misconception that being an artist means making a living from your art, exhibiting in galleries, or gaining public recognition. However, for many of us, artistry is about expressing ourselves creatively, consistently, and authentically. As Irwin (2003) highlights in her work on the artist-teacher identity, the act of making art is deeply entangled with pedagogical practice. To me, journaling is a ritual of artistic expression, a space for thinking, reflecting, experimenting, and being vulnerable.

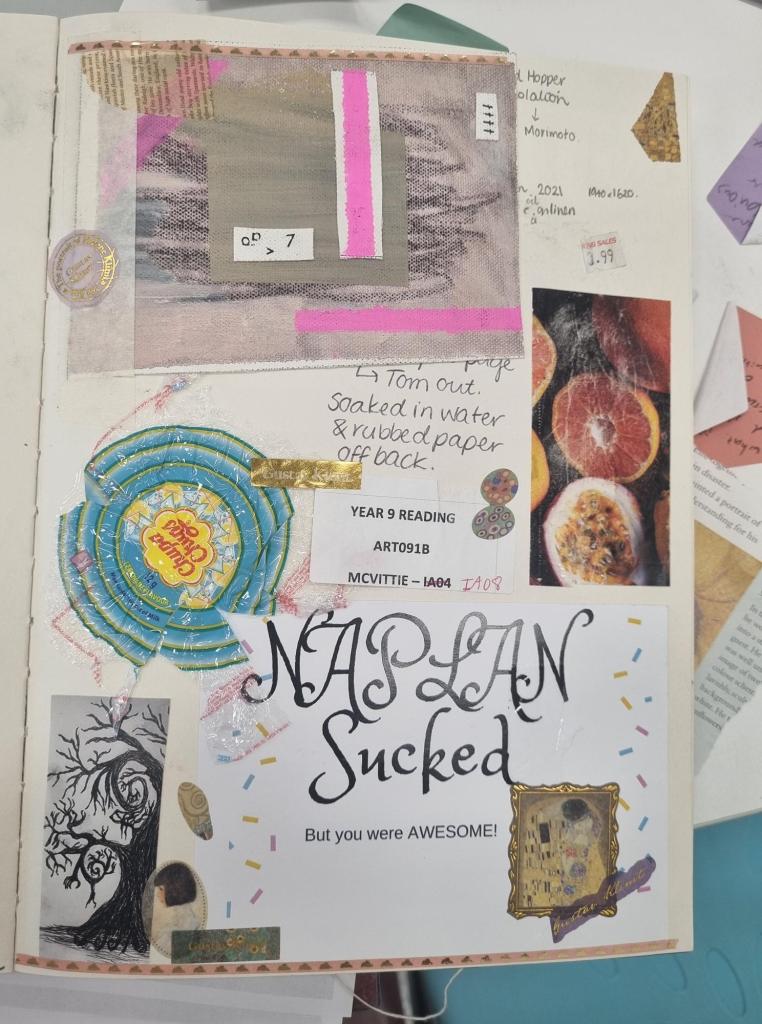

I’ve kept journals since I was a child, starting with “Dear Diary” entries and evolving through teenage years into visual and emotional collages: drawings of how I felt, letters, photographs, wrappers, and artefacts of my lived experience. Through my Art and Education degrees, these journals became more sophisticated, but their role never changed. They remained my personal archive, documenting my life, creativity, and growth. Every journal I’ve kept since Year 10 still sits on my shelf.

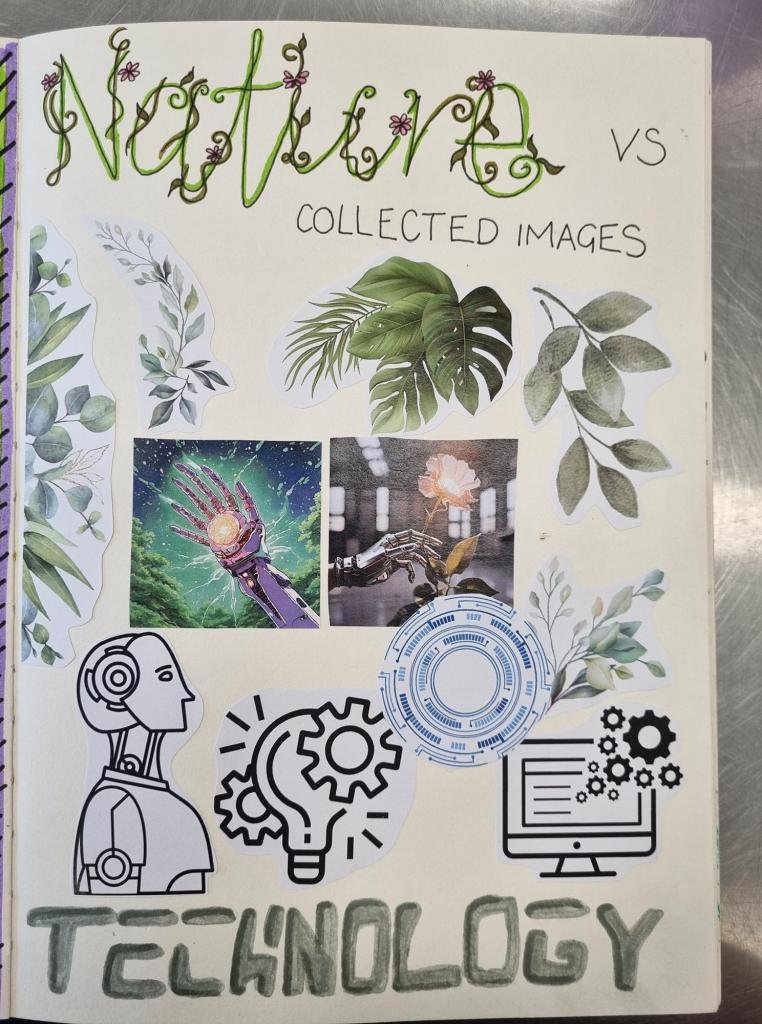

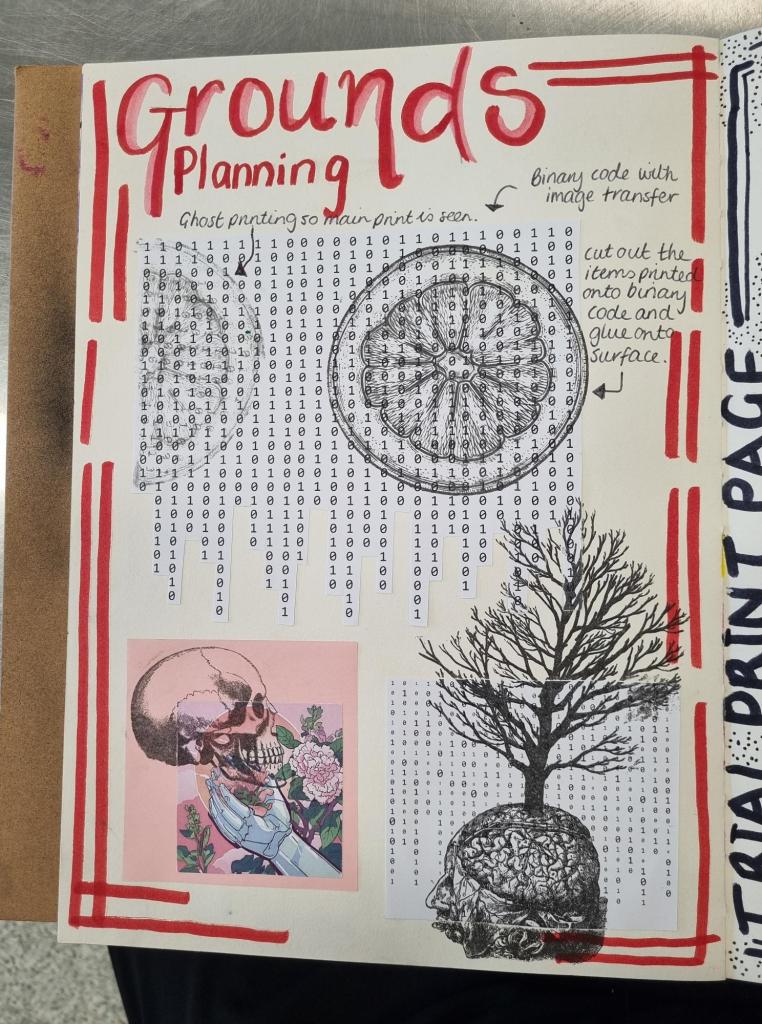

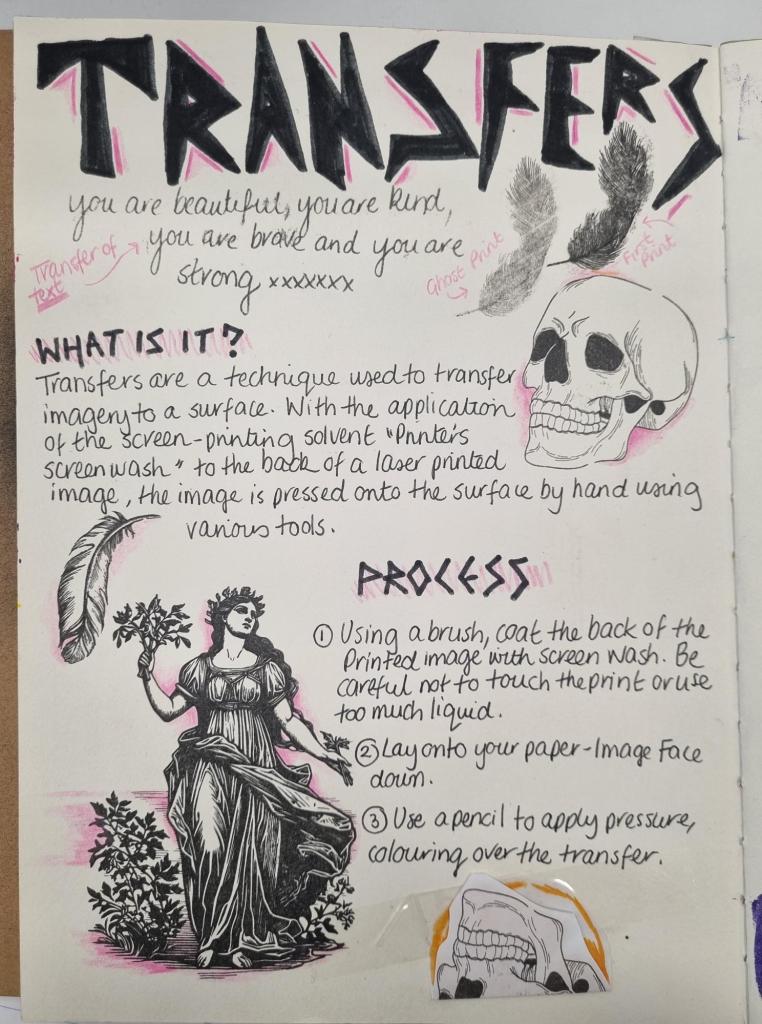

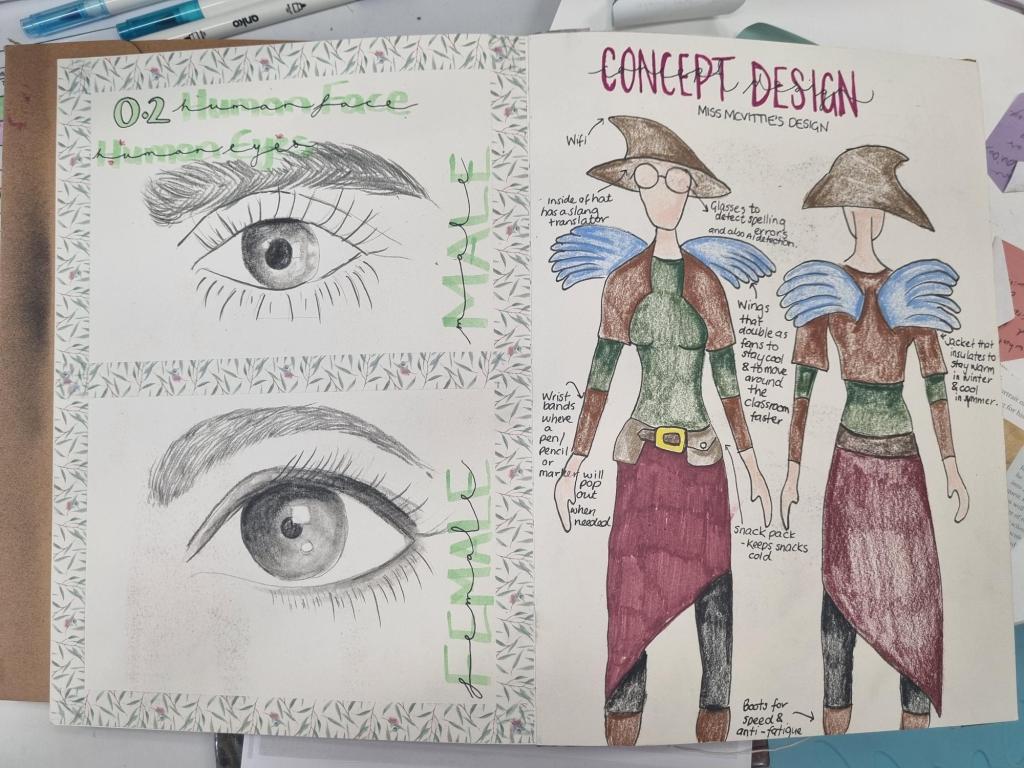

In the classroom, my teacher art journal has become a pedagogical tool that allows me to visually model processes for students, reflect on teaching practices, and maintain my own creative identity. Research has shown that modelling vulnerability and creativity fosters student engagement and trust (Daniel & Stuhr, 2006). When students see me making mistakes, experimenting with layouts, or altering tasks mid-way, it helps them recognise that artmaking is a process, not a product. As Eisner (2002) argues, the arts are uniquely positioned to teach critical thinking and flexibility through iterative making and reflective practice.

Journaling fosters this space. It offers an opportunity for creative risk-taking, ideation, and productive failure. In an age where students often focus on aesthetics and perfection, my journal helps deconstruct those expectations. I encourage my students to embrace messiness, mistakes, and experimentation as essential 21st-century learning dispositions, skills that extend far beyond the art room (Craft, 2005; Hetland et al., 2007). Rather than producing flawless pages, I ask students to show evidence of thinking, connections, and process.

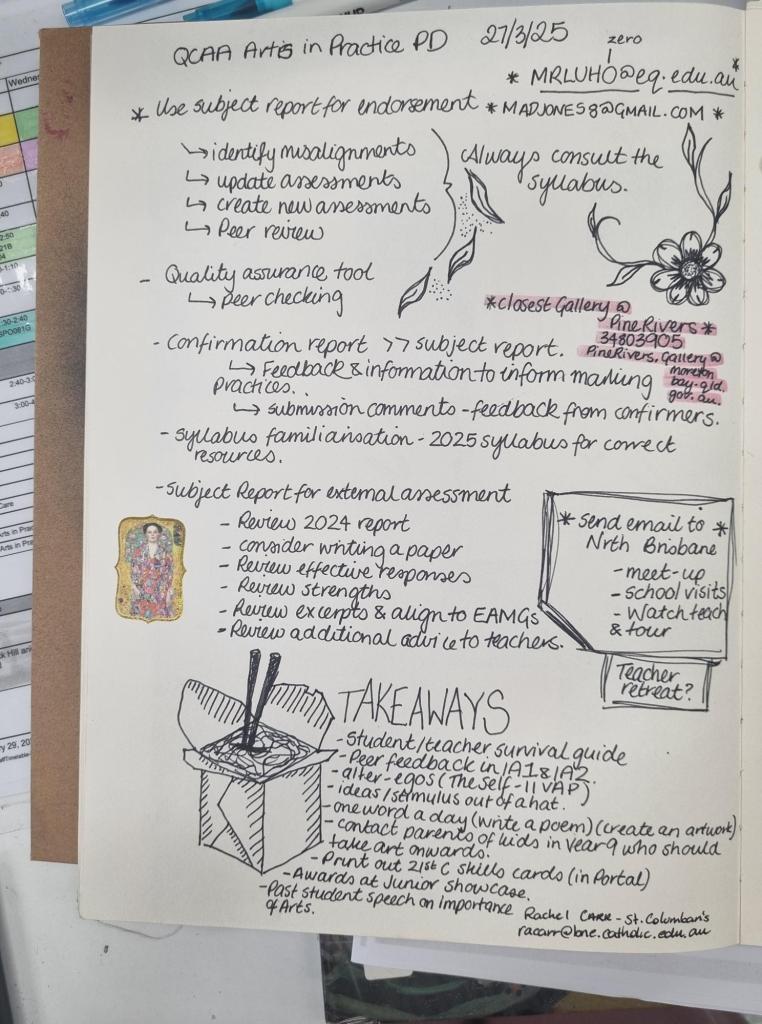

As a visual learner, I use my own journal to model tasks in real-time. If students are expected to complete an artmaking challenge, then I do it too. This provides insight into how a task might unfold, highlights opportunities for differentiation, and sometimes leads me to revise activities altogether. There’s no rigid organisation to my journal; it flows with the rhythm of my classes. When I complete a page, I photograph it and share it digitally, on PowerPoints, OneNote, or our learning platform, giving students access to a tangible, teacher-created model.

The impact is powerful. Students appreciate the transparency, the relatability, and the shared creative journey. For those who feel overwhelmed by direct instruction, having access to my journal, placed on their desk, open to the relevant page, offers a quiet form of support, scaffolding their learning without pressure.

My journal also functions as a professional archive. I glue in artefacts from school life: lolly wrappers from staff meetings, thank-you cards from students, professional development notes scribbled in the margins. It captures the unseen aspects of teaching and anchors them in a creative, reflective space. When I need to revisit a resource or unit idea, I simply return to that year’s journal, clearly dated, layered with thought and intention.

Importantly, teacher journaling is not something I do in isolation. Within my Visual Arts team, all three of us use teacher journals, and we’ve embedded it into our shared pedagogy. When a new timetable is released, we meet and share our journals with each other, passing them around, exchanging ideas, and modelling different creative approaches. Where one teacher prefers polished layouts, another embraces experimentation and visual chaos. Our students benefit from seeing this diversity, recognising that there’s no single “right” way to be creative.

This shared practice also models our dual identity as artist-teachers. As Douglas and Jaquith (2009) argue, maintaining an active art practice alongside teaching supports wellbeing and professional self-efficacy. Our journals embody this balance, allowing us to stay connected to our artistic selves while navigating the demands of education. They are more than sketchbooks, they are spaces of reflection, experimentation, and care.

So, are we ever too old for an art journal? I’d argue we’re never too old. In fact, as educators and artists, we might need them now more than ever.

References

Craft, A. (2005). Creativity in schools: Tensions and dilemmas. Routledge.

Daniel, V. A. H., & Stuhr, P. L. (2006). Contemporary art and multicultural education. In P. Duncum & T. Bracey (Eds.), On knowing: Art and visual culture (pp. 36–45). Sense Publishers.

Douglas, K., & Jaquith, D. (2009). Engaging learners through artmaking: Choice-based art education in the classroom. Teachers College Press.

Eisner, E. W. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. Yale University Press.

Hetland, L., Winner, E., Veenema, S., & Sheridan, K. M. (2007). Studio thinking: The real benefits of visual arts education. Teachers College Press.

Irwin, R. L. (2003). Toward an aesthetic of unfolding in/sights through curriculum. Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies, 1(2), 63–78.

Leave a comment